Google or Tools Get Time of Finding Final Solution

Global warming has all but guaranteed that storm seasons will continue to intensify, in traditional hurricane hot spots and further afield, meaning more people are likely to be affected by destroyed homes and communities and in need of financial support. But there is never enough support to go around, so charities are always looking to donate as efficiently as possible. A partnership between GiveDirectly and Google.org aims to smooth the process of delivering funds to the people who require them most urgently.

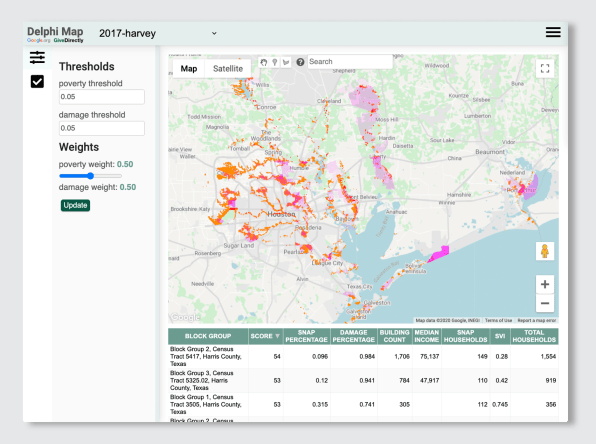

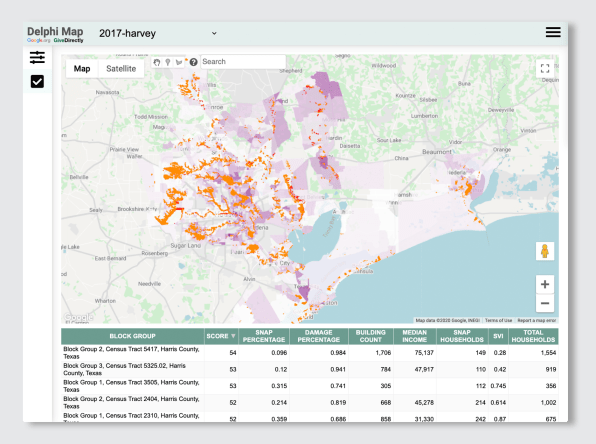

The charity, the largest in the world that assists via direct cash transfers only, and the tech giant have launched Delphi, an online tool that allows aid organizations to pinpoint the specific locations, down to granular zip-code level, most in need of assistance. The data-driven effort creates scores based on the overlap between two metrics—poverty level and destruction of property—then ranks and shows those neighborhoods visually in Google Maps.

It could prove crucial for nonprofits such as GiveDirectly, which has to make hard decisions about where their cash would go the farthest. Landing on a better method became a priority after many organizations, including GiveDirectly, largely ignored the hard-hit community of Port Arthur after 2017's Hurricane Harvey, in favor of concentrating on Houston. It later emerged that three out of five most impacted people were residents of Port Arthur (three years later many residents are still homeless and awaiting aid).

The organization used the tool retrospectively to assess their distribution efforts for Harvey, which caused approximately $125 billion worth of damage. "In retrospect, if we had had the tool, we would have been able to make sure that these marginalized communities were not missed," says Alex Nawar, humanitarian director at GiveDirectly.

Before the development of the new product, GiveDirectly principally used on-the-ground techniques to find the most crippled communities. They relied on media coverage, phone calls, on-the-ground searches, and information collected by other organizations. That proved to paint inaccurate pictures, often leaving less visible communities disregarded. "This tool would have really made sure that no one was left behind because they were not part of the narrative, or not part of the word-of-mouth campaigns," Nawar says.

A team of four Google Fellows developed Delphi (named after the ancient Greek shrine that was home to an oracle who could predict the future) over the span of six months. They used Earth Engine, Google's geospatial data viewer, explained Julie Xia, one of the fellows, and plugged data into it. They used census block data for locations, SNAP (food stamp) data for poverty levels, and data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration for property damage (NOAA also produced high-resolution satellite imagery that can be viewed on top of the maps). Users can set thresholds (such as at least 30% of the population on SNAP or at least 50% of the region damaged) and weight the metrics as required.

GiveDirectly would then target those communities with direct cash relief. The charity only sends money transfers, typically on prepaid debit cards, because that allows people to decide for themselves how to spend the money on recovery. Sending clothing, for instance, can clog up supply lines; food donations can go bad; and it's hard to donate vital items such as building materials. It's also simply less patronizing. "Traditional aid has some paternalistic bent to it," says Alex Diaz, head of crisis and humanitarian response at Google.org, "but the notion of direct cash transfer, at its core, acknowledges the dignity and agency within recipients."

Delphi, which is now live, will not be limited to GiveDirectly. It has the framework to be used not only for hurricanes but also for other disasters, such as wildfires. Nawar adds that it'll also save aid organizations time, and field costs by about 25%, by cutting back on the laborious fieldwork. Recently, the American Red Cross expressed interest in trialing it, and Diaz hopes—having made it open-source and easy to use—that it'll ultimately benefit the humanitarian sector as a whole.

Google or Tools Get Time of Finding Final Solution

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/90558331/this-new-tool-pinpoints-the-communities-most-in-need-of-disaster-relief